SAVE UNESCO'S

WORLD HERITAGE SITES

Kinabalu National Park is located on the northern end of the island of Borneo (in the district of Ranau) in the State of Sabah in East Malaysia. The National Park is dominated by Mount Kinabalu which at 4,095-metre (or 13,435 feet) above sea level is the highest mountain between the Himalayas and New Guinea, the third highest peak of an island on Earth, and 20th most prominent mountain in the world by topographical prominence.

At just 88-km away from Kota Kinabalu city, the Park was gazetted in 1964 and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000.

Even until this day, Mount Kinabalu’s name remains shrouded in mystery. From 1851 when Hugh Low and other climbers attempted the first recorded ascent, they had observed the local guides were carrying an assortment of charms and performing religious ceremonies upon reaching the summit. Since then, there have been several traditional Kadazan/Dusun myths and legends recorded that tell the story as to why the guides revered and respected this ancient monolithic giant so much and why it has been named as it was.

Known as North Borneo, the territory was originally established by concessions of the Sultanates of Brunei and Sulu in 1877 and 1878 respectively. It was ceded to the crown colony as a British Protectorate in 1946. In 1963, Sabah merged with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore to form Malaysia.

The Kinabalu Park was discovered by British colonial administrator and naturalist, Hugh Low in 1895, during a serendipitous expedition from Tuaran to Kundasang.

Outstanding Universal Value (OUV)

As Malaysia’s first World Heritage Site declared by UNESCO in December 2000, Kinabalu Park is recognized for its 'outstanding universal value' and its role as one of the most important biological sites in the world. Kinabalu National Park was gazetted in 1964 to protect Mount Kinabalu and its plant and animal life, covering an area of 754 sq.km and incorporates two mountains, Mount Kinabalu (4,095 metre) and Mount Tambuyukon (2,579 metre).

In inscribing Kinabalu Park as a World Heritage Site, UNESCO recognizes Kinabalu Park as one with “natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity” under two criteria for its selection.

Mount Kinabalu, along with other upland areas of the Crocker Range is well-known worldwide for its tremendous botanical and biological species biodiversity with plants of Himalayan, Australasian, and Indo-Malayan origin.

A recent botanical survey of the mountain estimated a staggering number of 5,000 to 6,000 plant species (excluding mosses and liverworts but including ferns), which is more than all of Europe and North America (excluding tropical regions of Mexico) combined.

Additionally, there are found to be 326 species of birds, over 110 land snail species and more than 100 mammalian species identified. Among this rich collection of wildlife are famous species such as the gigantic Rafflesia plants and Orang Utans.

Identification of Threats

In 2020, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) which assesses the status of World Heritage nature sites noted that the conservation outlook for Kinabalu Park is “good with some concerns.” It noted limited degradation of the nature park including encroachment, introduction of non-native plant species and increased demand of tourist access. Generally, however, the IUCN noted that the current status of the Kinabalu Park “remains good” and is reasonably backed by adequate legislation and a state policy document.

The boundary of Kinabalu Park encompasses the two mountains including the remaining naturally forested slopes. It thus incorporates much of the natural diversity and habitats that constitute Kinabalu Park’s key natural heritage values.

As the soil condition for the steep mountainsides is not suitable for farming or for the timber industry, in this way at least, much of the habitats and animal life within its boundary have remained largely undisturbed.

Settlement and logging have occurred at the boundary in many places although the park’s limits are clearly marked and regularly patrolled. At the periphery, rainforests have been slowly cut down and degraded for timber, palm oil, pulp, rubber, plantations and mining of minerals. The increase in such activities is being matched by a growth in illegal wildlife trade, as cleared forests provide easy access to more remote areas.

Climate change is also likely to reduce the suitable habitats for certain plant and animal species.

The first major threat to Kinabalu Park is deforestation. Given that it occurs frequently and causes irreparable damage, we rate the risk posed as high according to the framework for threat assessments.

Illegal logging has become a way of life for some communities with timber being taken from wherever it is accessible, sold to collectors and processed in huge sawmills. In the absence of sufficient alternative economic development, this is an irresistible lure for the local communities.

Satellite studies have indicated that of the 76% of all forested land in 1973, only 29% remained intact by 2010, and 24% has been logged. Between 1985 and 2001, some 56% of protected (or more than 29,000 km²) lowland tropical rainforests in Kalimantan and Borneo were flattened to supply global timber demand and although protection laws are in effect throughout Borneo, they are often inadequate or are flagrantly violated, usually without any consequences.

Another big driver of deforestation is the growth of oil palm plantations in response to global demand for palm oil, the most important tropical vegetable oil in the global oils and fats industry. Oil palm development contributes to deforestation - directly and indirectly. About half of all presently productive plantations (over 6 million hectares) were established in secondary forest and bush areas in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Without the maintenance of very large blocks of inter-connected forest, there is a risk that hundreds of species could become extinct. Large mammals such as orangutans and elephants are particularly affected because of the vast areas they require to survive as is evidenced by the increasing number of Borneo elephants coming into conflict with the expansion of human agriculture activities in its natural habitat.

Other smaller species, especially small mammals, may not be able to recolonize isolated patches of suitable habitat and thus will become locally extinct. Road construction through protected areas leads to further separation of habitat ranges and provides easy access for poachers to some of the more remote and diverse tracts of remaining virgin forest.

It is not surprising that as tropical forests undergo drastic transformations, the species that rely on them are inevitably put at risk. Between 1973 and 2015, as forest was lost, much of this to oil palm and other industries, a study carried out in May 2020 by the Frontiers in Forest and Global Change has shown that 245 forest birds and mammals have lost approximately 28% of their habitats.

When left undisturbed, Borneo’s natural forests are not usually prone to fires. But as forests are opened up, they dry out and are increasingly susceptible to fires, which among other problems cause dangerous atmospheric haze. Fire and haze produce many adverse effects ranging from impacts on human health, short and long-term medical treatment costs, losses in tourism and forfeited timber revenue. Moreover, rampant poaching, assisted by the increasing number of roads and logging trails, poses a grave threat to Borneo’s endangered species. Wildlife crime is a big business. Run by dangerous international networks, wildlife and animal parts are trafficked like illegal drugs and arms.

Moreover, rampant poaching, assisted by the increasing number of roads and logging trails, poses a grave threat to Borneo’s endangered species. Wildlife crime is a big business. Run by dangerous international networks, wildlife and animal parts are trafficked like illegal drugs and arms.

Kinabalu Park has lost large proportions of forests at its boundary in recent years. Two modifications to boundaries have resulted in losses to integrity of Kinabalu Park. In 1970, for example, 2,555ha were excised to allow a copper deposit to be mined. Its locations are pinned white as shown in the right figure. This mine is now worked out but evidence remains.

In an international study led by the University of Queensland, it is one of the worst affected Natural World Heritage Sites with as much as 15,000 ha of its forests (about the size of 30,000 football fields) cleared between 2000 and 2012. The study revealed that the 203 Natural World Heritage Sites were some of Earth’s most valuable natural assets but many were deteriorating due to urbanisation, agriculture and logging.

The second major threat to Kinabalu Park is tourism. Since the threat posed also occurs frequently and causes direct damage, the risk can be rated as high.

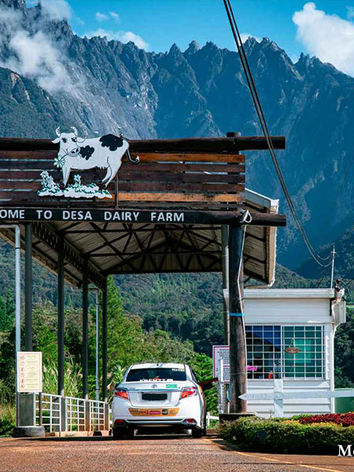

Mount Kinabalu is an extremely popular destination for tourists. Another factor making it a highly attractive destination, Kota Kinabalu is a cultural centre with a large indigenous population of the Kadazan (part of the Dusun Peoples) with distinctive cultural activities and practices that have been well-preserved.

Kota Kinabalu also offers world-class hotels, great seafood as well pristine beaches. In recent years, favourable currency exchange rate for the Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) makes Kota Kinabalu a very affordable destination.

It is not surprising, therefore, from 1965 to 2014, there has been significant growth in the number of number of visitors – both climbers as well as day visits. Admittedly, this increase has also resulted in significant living standards for the locals in terms of job opportunities, etc.

Hence, from the tourism perspective, the key management issues are the growing pressure from commercial tourism and the need for increased capacity building. Extensive planning and management will be required to ensure impacts within the park are limited as the number of visitors’ increases.

Assessment of Conservation Management Plans

As reported by IUCN in 2000, Kinabalu Park has performed well in protected area management but there are a series of concerns with that would require continuous planning, monitoring and responding to. The rugged terrain of Kinabalu Park automatically provides a high level of natural protection so the need for on-site intervention applies mainly to the edges of the World Heritage site where continued agricultural pressures at its periphery persist. There are also concerns with poorly planned or often haphazard infrastructure developments such as tracks, accommodation complexes and roads.

There have been occasional reports of encroachment in the form of illegal agriculture and logging; these, however, occurred outside the boundary of Kinabalu Park which has now been clearly marked and regularly patrolled.

When the park was first inscribed on the World Heritage List, it was noted at that time that the park is becoming an ‘island in a sea of agricultural land use.’ In 2011, the Sabah Environment Protection Association was highly critical of the illegal land clearing near the World Heritage Site and a recent study indicates that loss of forest cover in the surrounding area is ongoing. Although the boundaries remain rather permeable and Settlement, agricultural development, and logging continue to occur right up to the boundary in many places. There is hence an urgent need for the state authorities to carefully regulate development in key strategic locations outside the park where it still has control.

Implementation of strong protection and enforcement measures would ensure that the integrity of the property and its natural values are maintained. There is currently no requirement for buffer zones at the park’s boundaries.

In terms of tourism, some management strategies have been implemented. In 2016, the park authorities, for example, established the world’s highest 'via ferrata' infrastructure resulting in the sudden influx of tourists who do not have previous mountaineering experience now navigate to its summit or scenic sections of the park with great(er) ease.

As a publicly Environment Impact Analysis was not readily available, it remains unclear whether potential impacts on the park’s OUV was assessed or appropriate mitigation measures were implemented. One thing that most studies have confirmed is that due to the sensitivity of the location, certain fauna and flora have certainly been impacted.

With increased tourist numbers, there is a growing need for amenities including more paved areas to accommodate for wider roads, meeting areas, coach parking etc.; the latter having resulted in extensive soil erosion at many locations.

A recent study on the impacts of traffic noise on bird populations has also concluded that this has a significant impact in the vicinity of the property's main access routes. All these clearly show that there is a lack of basic planning, monitoring and reporting and must be greatly improved.

Suggested Conservation Management Strategies

In its 2020 Outlook Conservation Assessment Report, IUCN noted that the management of the Kinabalu Park is dependent on an outdated strategic document dated to as early as 1971. It also lacks clear objectives and prescription at the park management level, especially in regard to natural heritage values. A specific management plan is a clearly needed.

In 2002, an amendment to the document was proposed but there is no evidence to suggest that any steps have been taken to address the issue by late 2019 – this amidst increasing visitor arrivals, new tracks being added and the advent of climate change. While current management effectiveness appears to be reasonable, the lack of a comprehensive Development Master Plan to guide management of the property together with the absence of systematic monitoring limit the assessment of management effectiveness.

In terms of tourism specifically, it is also imperative that they must be educated about the way the indigenous people see the spiritual significance of the site they visit.

Capturing the headlines locally and internationally was the rare earthquake that occurred on 5 June 2015. Subsequent to the 2015 Earthquake, the government introduced an early warning system for earthquakes including for school buildings as well the setting up of a seismic centre to monitor earthquake activities in the state.

What is interesting that developed from the incident is not the earthquake itself but rather cultural sensitivity of the indigenous people/lack of understanding and respect for indigenous cultural history by the tourists to the local culture and beliefs when it was reported that six days before the earthquake, around ten Western tourists "stripped and urinated at the mountain” which locals believe have angered the spirit at the sacred place.

This provoked outrage among certain local citizens who wanted the alleged offenders charged in native court and to pay the sogit which is normally imposed on wrongdoers for the purpose of appeasing "the aggrieved", thus placating the community.

However, as most of the detained tourists have been released from Malaysia's prison and escaping native court, the local villagers performed their own rituals.

In terms of encroachment, the property would benefit from designation of buffer zones, assignment of highly appropriate and competent officers and supporting staff, strengthening the community support through a participation programme, and revising, enhancing, and strengthening the existing management plan using holistic planning process and approaches. All these are currently under active consideration. The property has been subject to extensive research and has an excellent collection of specimens along with sufficient research facilities. Integration of the results obtained from research and with the management actions and decisions will assist in ensuring the long-term conservation of the property and its unique and important natural values.

The End.

Bibliography

xxxxx